I left Datadog 2 weeks ago, after 5 intense and incredible years. When I joined, we were about 300 people strong, whereas the current headcount is now approaching 4000. If you never have experienced exponential growth, this is about as close as you can get to it! This means that we were close to doubling in size each year, whether in headcount, infrastructure size, number of teams, and complexity.

About 2.5 years after I was hired, Datadog became a publicly traded company.

In this article, I will explain the impact this had on me, both financially and psychologically, as transparently as I can. The intention is to examine how such an event can change one's life, positively and not, and give you some return of experience on the choices that I made.

This is a weird and personal article. It is about the stock market, how stock options work, psychological paralysis, burn-out and life choices. I hope some of it can be useful to you, but really, this is also something I needed to write for my own catharsis.

How it started

When I joined, back in 2017, the first thing I had to do was choose between 3 compensation packages:

- higher salary and lower equity (36000 stock options)

- medium salary and medium equity (48000 stock options)

- lower salary and higher equity (60000 stock options)

I chose the first one, as I didn't really understand what stock options were. I held the financial world pretty much in contempt, and chose what I could understand: actual money in my bank account at the end of the month. I felt that there was about a 0% chance these stock options would be worth anything anyway, so choosing the highest salary was the safest move I could make.

Wait. What is a stock option anyway?

Finance is fraught with lingo. Yes, possibly even more than technology. So before diving into how the stock market affected my psyche, let's try to define a couple of terms.

A stock is a financial instrument representing the ownership of a fraction of a corporation. These shares are bought and sold on stock exchanges (e.g. Nasdaq, Euronext, etc). For example, should I want to, I could currently buy a share of Amazon.com Inc. (referenced as AMZN on the market) for 2,107.44 USD on the Nasdaq, which would make me a (tiny) shareholder of Amazon. The price of said share varies according to demand and offer, basically.

There are multiple reasons why one should want to hold stocks: either the stocks they own give them voting rights at the company annual meetings, allowing them to influence how the company is managed, or maybe they hope to make a profit by selling at a higher price than the one they bought the stock at.

Now, onto stock options. A stock option is the opportunity to acquire a stock at a guaranteed reduced price. That reduced price is called the strike price, and should be part of your employment contract. In my case, that strike price was $0.85. That meant that should I want to acquire one of these 36000 stocks, I needed to give Datadog 85 US cent.

The word option really means that you can decide to purchase these stocks coming with a discount, but you don't have to. You have the option to do it.

Obviously, companies don't grant all stock options to their employees immediately after hiring, because new employees could decide to stay for a couple of days, pocket all their stocks and then move on. What happened in my case (which I hear is pretty common, really) is that I unlocked (the real term is vest) stock options according to a vesting calendar. I didn't get anything for a whole year, and then I unlocked (vested) 25% of my stocks in one go. It's called a one year cliff. After that, I vested 6.25% at the end of every quarter for the remaining 3 years.

Once a stock option was vested, I could then wire money to Datadog and acquire the stock at the reduced price. This is called exercising the stock option. At that point, the stock options were really converted into a stock, of which I was the owner.

Phew. Let's recap.

By staying at Datadog, I had the opportunity to regularly wire my employer money in order to acquire stocks (i.e. to become a shareholder) at a reduced price, according to a 4 year calendar, in the hope of making a profit later.

strike price = f(risk)

The central notion here is risk. If you join a startup in its infancy, the probability of you turning a profit on your stock options is infinitesimal. To counteract the odds, you will probably get a very low strike price and many stocks, whereas if you join a company on the verge of going through its IPO, you probably will be given less stocks at a much higher strike price. The reason is simple: companies want to reward employees who took the risk of buying in early.

In my case, I joined Datadog when the probability of an IPO was still very low, which was reflected in my strike price.

What will buy you bread vs what might buy you a house

Fast forward 2 years. There are now more and more internal rumors about a potential upcoming IPO. These rumors culminate into the subject being publicly discussed in an all-hands. We are told that we are indeed going through the IPO filing process, which could take many more months before it comes through, if it does. One point is hammered in: nothing is sure at that point. Everything could still fail.

Immediately after the announcement, a seemingly never-ending stream of questions are being raised by employees. What strikes me is every question asked by one of our American colleagues seem well-informed. Many of them seem to have gone through an IPO before, and even those who have not seem to understand how these things work. The same cannot be said for my French colleagues and myself. We are collectively clueless. At that point, I hadn't even exercised a single stock option, as I was still fearful of committing thousands of euros in what could be a pipe dream.

I decide to ask one of my American teammates for advice. When I tell him that I still haven't exercised anything, he pauses for a second, and then proceeds to tell me the following.

Look. I'm not going to tell you what to do, but here's what I do. Every time I vest, I exercise immediately after. Every time. My salary is what buys me bread. My stocks are what might buy me a house.

After that conversation, I started to dig into the relationship between the exercise date and taxes, and proceeded to exercise everything that I had vested until then once things became clearer.

Hey Mr Taxman

Everything I say here applies to my understanding of the French tax code. I am not a lawyer. Do not take this as financial advice.

To understand why my colleague would always exercise right after his vesting date, you first need to understand how stocks are taxed. The way this works in France is pretty similar to the way the IRS does it in the US. If you live in Cyprus, Paraguay or any other tax haven, you don't pay any tax on stocks, which is good for you and sad for your hospitals and roads.

There are 2 things to consider:

- if you exercise a stock option, you acquire a stock at a reduced price. You virtually made money there, because you should have paid more for the stock, meaning you will pay taxes on this virtual gain. This is call the acquisition tax ("gain d'acquisition" in French).

- if you make a profit selling your stock, you will pay taxes on said profit. This is called profit tax ("gain de cession" in French).

To understand how this works, let's take an example. Say my strike price is set to $1. I exercise a stock option when the value of the associated stock is $10, and I then sell it later on the market for $40.

- I will pay acquisition taxes on the $9 difference between the regular market price and the strike price

- I will pay profit taxes on the $30 difference between the sell price and the regular market price at the time of the purchase

This means that the sooner I exercise, the smaller the difference between the exercise and strike price should be, meaning the smaller my acquisition tax will be in the end (following the hypothesis that the stock price does nothing but grow, which was true for us for a while).

In the case of a stock option related to a stock that is not publicly traded yet (pre-IPO), the "regular market price" considered when calculating the acquisition tax is set to the stock FMV. The FMV is a theoretical price the stock would have, according to some independent third party appraiser, that is regularly updated.

In our case, the FMV was updated every quarter and did nothing but go up until the actual IPO. The initial reasoning stood: the earlier my coworker exercised, the less acquisition tax he ended up paying.

At that point, the FMV was at about $9 and I decided to follow his advice.

Liftoff

This is the point in the article where I stop boring you with financial minutiae and start getting into how the IPO process affected me psychologically.

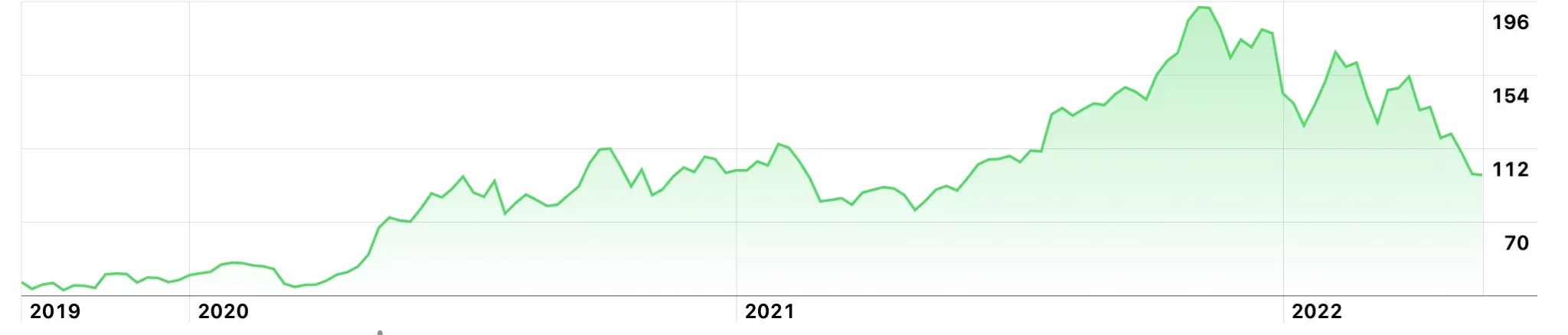

The IPO went really well. DDOG went from $27 to about $42 in a single day, and everyone celebrated. The trouble started the next day, when I configured my mac to display the stock current value in a sidebar widget. If you're at all familiar with addictology, this is where you start wincing hard.

I can't overstate how much of a bad idea this is. Having the feeling of "winning" or "losing" multiple times a day is addictive. The whole thing felt like a game, and I started to check my "Potential Benefit Value" in etrade several times a month. The numbers were in the 7 digits, and felt unreal.

Let's pause for a second, and imagine yourself sitting at a casino table. You're on a strong start, the odds are in your favor, and your chip pile grows pretty fast. Now, until you cash out, these chips are monkey money. They are worth nothing, and are only worth something if you take the decision to take them out of the table. You've won most of your games, so every time you lose one, you convince yourself to stay at the table to try and wait until to at least get back your losses. But then you lose some more, but hey, you should not back out now when you were winning so high not too long ago. On and on, in a loop. And so you stay at the table.

And that, dear reader, is why I think the casino pretty much always wins.

Here are a couple of things I learned in the last years, that were paramount in fighting off that psychological paralysis:

- The money you have invested on the market is not real money. It's worth nothing until you sell.

- Never put money in the market you can't afford to lose.

- Know when to check out. This means knowing what you would like to use that money for, how much your plan would require and selling when you reach it.

The money that could buy bought me a house

In 2020, we were collectively struck by The Great Plague, and everybody was stuck inside. At that point, I realized that I had golden opportunity of being able to buy a house in the area that my fiancee and I dreamt of living in, instead of being boxed in a small flat.

And what happened then was... nothing. I was looking at other tech-company stocks that were benefiting from the lockdown, such as Zoom, Docusign, Shopify, etc, and they were miles ahead of where Datadog was. All I had to do was wait! (rubs hands).

This is when my fiancee kind lost it with my shenanigans, and told me that we could be living our dream today instead of waiting for.. what exactly? More money? To do what?

Can't enough be enough?

she told me.

At that point, I knew that however high the stock price was, I was going to be too paralyzed to do anything else than looking at monkey money numbers anyway. And so I estimated how much cash I'd need to cover the house as well as the acquisition and profit taxes, kept a healthy margin in case my tax estimates were wrong (remember the thing about me not being a fiscal advisor?) and for the unescapable renovation work that would need to be done, and sold about 60% of my total stocks at $66.6 (hell yeah).

And just like that, I had enough to afford our dream, pay the taxes on it, as well as supporting my close family.

"Now, what about the remaining 40%?" an astute reader might ask? Well, that I could afford to lose, and didn't have any specific plan in mind for. They are still in the market, and are worth a pretty hefty sum of money. I didn't feel like I needed to convert them into cash for anything. If their value rises, good, if not, it might rise again, who knows?

And with that, I was done. Or so I thought.

Just when I thought I was out, they pull me back in.

Do you know what happened at the end of my 4 year vesting period? Here's what I thought was going to happen: nothing. However, what really happened was an impromptu conversation with my Director, telling me that Datadog was giving me a refresher, in the form of a 4 year vesting with a one-year cliff calendar for about 2000 RSU.

Aaand, back to financial minutiae just for a bit. RSU are "free stocks" the company gives you. You don't have to buy them (contrary to stock options). So you get new stocks just by staying around and doing your job. As they are way less risky than stock options, because the company has already IPO-ed, you also get less of them.

Where things started to get really psychologically tricky for me, is when 2 events coincided:

- I started to feel the symptoms of a burn-out, as I was working pretty hard, and had to deal with renovation work in the house, organizing our wedding (which was lovely, thank you very much), and various other fun things

- For various reasons that I won't go into, I was given 2 more RSU grants, on overlapping vesting calendars

After 5 years, I was at a crossroads. The more I went on, the more I felt I needed to slow down. Years of exponential growth and on-call were taxing on my mental health. I was constantly stressed out and on edge. I did not sleep well, was taking on weight and was overall losing interest in my work.

As I saw it, my two options were:

- I could stay and get more stocks, make more money, and continue working (with great and talented people!) in an ever-exponentially growing company that was promising me a promotion to Engineering Manager (which itself probably meant more stocks, less personal time and more stress), or

- I could decide to quit, rest, slow down and do something else.

I just want to be clear there. There were other options, such as going back to an IC role, that I discussed with my manager. I don't want to come across as passively dissing him. He truly was an incredible manager. But in the end, these were the 2 extreme options.

As I was slowly coming to the realization that option 2 was the one for me, came an extremely toxic thought. Was there a point in the near future where I'd vest a substantial amount of RSUs, after which I could then quit? The answer was yes, about 10 months from then. And thus I tried to stick around, feeling more and more depressed and disengaged, all that in the prospect of vesting stocks amounting to about $150,000.

Don't get me wrong, this is a substantial amount of money, that most people aren't privileged enough to dream about. Except that I didn't need it really. I was already living where I wanted, with my wife that I loved with all my heart. This was the endgame. I quickly realized that I was putting my mental health in harm's way just because I didn't want to feel like I was checking out of the table and leaving money on it. Money that I didn't really need in the first place, thanks to my remaining 40%.

Realizing how unhealthy that line of thinking was, I settled on option #2, negotiated a 2-month leaving period (the legal one in France is 3 months), after which I said good-bye to all the wonderful people I had been lucky to work with for years.

On my last day, my "Potential Benefit Value" in etrade was at about $1.2M. I left it all on the table.

And you know what? I'm happy. Enough was enough.

Comments